The Transatlantic Slave Trade

Between 1501 and 1867, nearly 13 million African people were kidnapped, forced onto European and American ships, and trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean to be enslaved, abused, and forever separated from their homes, families, ancestors, and cultures. The Transatlantic Slave Trade occupies a painful and tragic space in world history. It dramatically altered the global landscape and created a legacy of suffering and bigotry that can still be seen today.

- About

- museum

- get involve

Key Aspects of the Trade

Enslavement has existed throughout human history in various forms. These include imprisoning people during wars or due to their beliefs. However, permanent, hereditary slavery rooted in race—later practiced in the U.S.—was uncommon before the 15th century.

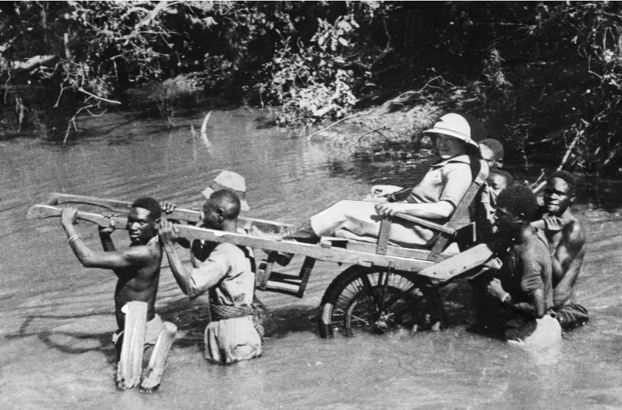

The nature of slavery started to shift as European settlers, focused on colonizing the Americas, employed violence and military force to force enslaved individuals into labor. Indigenous peoples were the initial victims of this forced labor and enslavement by Europeans in the New World. Unfortunately, millions of Indigenous people also perished due to disease, famine, wars, and brutal working conditions in the subsequent decades.

European powers, focused on profit from their American colonies, expanded their reach to Africa. To satisfy their increasing labor demands, they launched an unprecedented global enterprise involving abduction, human trafficking, and racialized slavery. This scale of kidnapping and trafficking over such vast distances had never occurred before.

The Impact of Europe on Africa

Europe had no prior contact with Sub-Saharan Africa until the Portuguese, driven by the pursuit of wealth and gold, sailed along Africa’s western coast and arrived at the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) in 1471. Initially aiming to acquire gold, Portugal established trade partnerships and constructed El Mina Fort to safeguard its interests in the gold trade.

The gathering of European nations in Sub-Saharan Africa initiated a brutal process that combined advanced labor exploitation, global trade, widespread enslavement, and a complex race-based ideology, leading to the development of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Over the following decades, Spain, England, France, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Sweden began to establish contact with Sub-Saharan Africa. Portugal quickly transformed El Mina into a prison for detained Africans. At the same time, European traffickers constructed castles, barracoons, and forts along the African coast to facilitate the forced enslavement of abducted Africans.

German and Italian merchants and bankers, though not directly involved in trafficking kidnapped Africans, played a crucial role by offering funding and insurance that supported the development of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and plantation economy. Italian merchants significantly contributed to extending the sugar plantation system to Atlantic Islands such as São Tomé, while financial capital from Genoa was vital in boosting Portugal’s capacity to transport Africans.

By the 1600s, all major European nations had built trade links with Sub-Saharan Africa and were involved in transporting kidnapped Africans to the Americas. During this era, a few thousand Africans were abducted and trafficked to Europe and the Americas, but the scale of human trafficking quickly grew to horrific levels.

European powers, primarily led by Portugal, started colonizing the Americas in the 1500s. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans exploited land taken from Indigenous peoples to establish plantations that relied on enslaved labor to produce large quantities of goods, mainly sugarcane, for trade and sale. The demand for mass-produced sugar fueled the increase in the forced movement of Africans through the transatlantic slave trade.

Initially, Europeans depended on Indigenous peoples for labor. However, widespread killings and diseases devastated Indigenous populations, one of the most significant known population losses in human history.

The Indigenous population in Mexico declined by nearly 90% over 75 years. On Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), the Arawak and Taino populations decreased from an estimated 300,000–500,000 in 1492 to fewer than 500 by 1542, within just five decades. With no Indigenous workers available, plantation owners across the Americas became increasingly desperate to find new sources of exploited labor.

Motivated by greed for wealth, these European nations transitioned from collecting gold and goods in Sub-Saharan Africa to engaging in the slave trade. Over the centuries, Europeans insisted on transporting millions of Africans to labor on plantations and in various industries in the Americas.

Slavery already existed in Africa before, but the European commodification of human beings was completely new and significantly transformed the African understanding of enslavement.

Although some African officials and merchants gained wealth by exporting millions of people, the Transatlantic Slave Trade severely damaged and destabilized societies and economies across Africa. The widespread disruption and violence fueled long-term conflicts on the continent, while European powers profited immensely and strengthened their global dominance from this inhumane trade.

The Iberian powers of Spain and Portugal, along with their colonies in Uruguay and Brazil, were responsible for 99% of the nearly 630,000 Africans kidnapped and trafficked from 1501 to 1625. Over the subsequent 240 years, other nations such as England, France, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and the Baltic States, including their colonies, also participated in the trafficking of Africans. From 1625 to 1867, almost 12 million kidnapped Africans were trafficked. Notably, ships from Portugal and its colony, Brazil, alone transported 5,849,300 Africans during this period.

Ships from Great Britain were instrumental in the transatlantic slave trade, accounting for more than 25% of all Africans taken between 1501 and 1867. From 1726 to 1800, British ships spearheaded the transportation, capturing over two million Africans.

Between 1626 and 1867, ships from North America were involved in the trafficking of at least 305,000 enslaved people from Africa. In the two years prior to the U.S. banning the international slave trade in 1808, a quarter of all trafficked Africans were transported on ships flying the U.S. flag. Rhode Island’s ports coordinated voyages that trafficked at least 111,000 kidnapped Africans, ranking it among the 15 largest ports of origin worldwide.

Slave shackles were iron restraints, often heavy cuffs for ankles or wrists, used to physically control, punish, and prevent escape among enslaved people during the transatlantic slave trade, symbolizing brutal dehumanization. Types such as the foot shackle, as shown below, were common on slave ships and plantations and were designed to inflict suffering and break resistance.

An image of a slave shackle

The abduction, abuse, and enslavement of Africans by Europeans for nearly five centuries dramatically altered the global landscape and created a legacy of suffering and bigotry that can still be seen today.

The Cruelty of the Middle Passage

The horrific conditions of the Middle Passage meant that of the more than 12.5 million Africans kidnapped and trafficked through the Transatlantic Slave Trade, only 10.7 million survived the journey.

Between 1500 and 1820, eighty percent of those who embarked for the Americas were kidnapped Africans, who far outnumbered European immigrants.

Almost two million Africans died during the Middle Passage—nearly one million more than the number of Americans who have been killed in every war fought since 1775 combined.

Numbers like these can measure the scale of the harm, but they do not capture the horrific and torturous experience of those who died, nor the trauma carried by the 10.7 million Africans who endured the weeks-long journey.

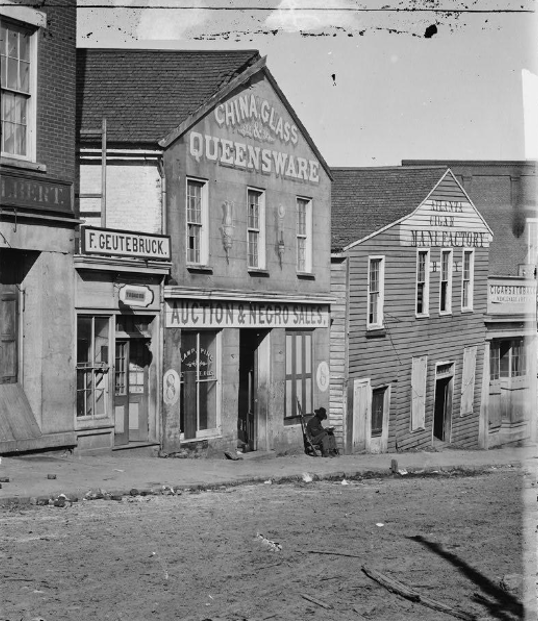

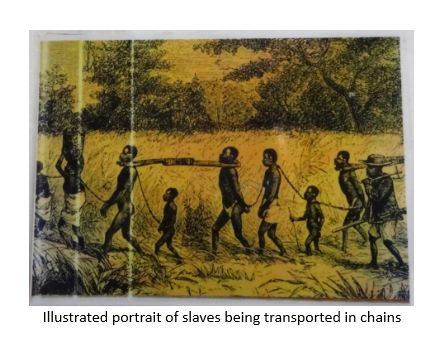

Some enslaved individuals were taken from West Africa’s coast and sold to European slave traders. For most captives, the journey of Transatlantic trafficking started weeks, months, or even years before they reached the shore. Driven by high demand from white enslavers and traders, African kidnappers ventured inland to kidnap people from villages and towns. In the 18th century, about 70% of Africans involved in the Transatlantic Slave Trade were free individuals forcibly removed from their homes and communities. They were often made to walk, chained together in a coffle, for dozens or even hundreds of miles until they arrived at the coast.

Along the coast, kidnapped Africans were held in barracoons, slave pens, and dungeons within prison castles, waiting for the ships that would transport them across the Atlantic. They were made to board slave trading ships that remained docked—sometimes for months—until enough human cargo was loaded, making the voyage profitable for the enslavers. While specific death toll records are unavailable, scholars estimate that the mortality rate among those confined in barracoons and on docked ships was comparable to Europe’s fourteenth-century Black Death, which killed at least 40% of the continent’s population.

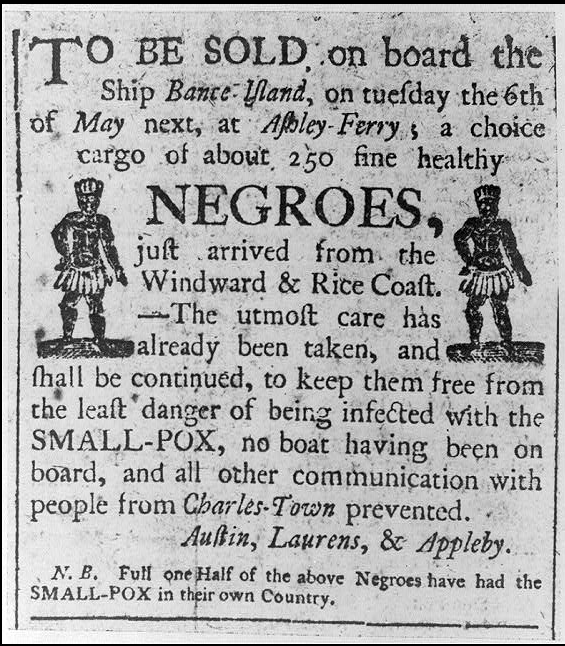

African captives faced invasive, dehumanizing examinations before boarding enslavers’ ships. Women, men, and children were stripped, inspected, and sometimes molested to assess if they were suitable for hard labor and reproduction.

Traders aggressively touched the breasts, buttocks, and vaginal areas of women and young girls, purportedly to evaluate their fertility. Men and boys were also molested around their groin, scrotum, and anus. One white trafficker later testified that the process resembled how he would handle “a horse in this country” if he were about to buy it.

Captives were numbered and loaded onto ships, separated by gender, and packed tightly into the holds under harsh conditions. Men were usually restrained in ‘spoonways,’ naked and forced to lie in urine, feces, blood, and mucus, with little fresh air.

Trafficked Africans were chained and forced to lie for weeks during their journey, unable to stretch or stand except for brief periods on deck. The poor conditions fostered disease and vermin, with some captives suffocating due to insufficient air below deck. In certain ships, the death rate reached as high as 33%.

About 15% of kidnapped Africans—nearly two million people—died during the Middle Passage.

African women and girls endured similarly horrific conditions in the hold and were uniquely terrorized by the crew. Forced to be naked and segregated from the men, they lived in constant fear of rape or assault by white sailors, who often used sexual violence and flogged those who resisted. Cruelty and terrorism were widespread on trafficking vessels run by Europeans. Sailors used brutal punishments for minor offenses to remind others of their authority.

These painful conditions persisted for weeks and sometimes months. A typical journey lasted five or six weeks, while some extended to two or three months. Longer voyages resulted in increased mortality among the captured Africans on board.

When ships arrived at ports across North and South America, the surviving Africans from the Middle Passage faced further examinations and abuse by enslavers before being sold and compelled to perform grueling labor, often leading to their premature death. Approximately 80% of kidnapped Africans transported via the Middle Passage were forced to work on sugar plantations in extremely hazardous conditions, resulting in high mortality rates.

Slavery in the Americas

About 90% of the enslaved men, women, and children who endured the Middle Passage reached the Caribbean or South America. Slavery in the Americas was governed by the Portuguese, Spanish, French, British, and Dutch, each of whom implemented distinct political, legal, and cultural practices. These differences contributed to the diverse development of slavery across the region and influenced the social construction of race and racial hierarchy.

Comparing the severity of slavery across the Americas is pointless, as its brutality was universal. Conditions in South American and Caribbean colonies were especially terrible—most enslaved people there worked on sugar plantations, known for their brutality. Labor was exhausting, involving long hours of gang work starting early at 5 a.m. and continuing until dusk, often under dangerous conditions. Portuguese plantations in Brazil had higher death rates and shorter life spans than those in the U.S.

The experiences of enslaved men and women across the Americas were shaped by factors specific to each European power and its colonies. In the North American colonies and later the U.S., white populations were the majority in most areas, except in South Carolina and Mississippi. Conversely, in South America and the Caribbean, nonwhite populations often made up over 80%.

When the Haitian revolution began in August 1791, white Europeans constituted only 7% of the population, with free people of color roughly equal in number to Europeans. In South America, Iberian dominance was challenged by a rising enslaved population, which frequently demanded freedom in exchange for fighting Indigenous opponents resistant to European colonization. In these colonies, the danger of rebellion by the minority white population played a vital role in shaping society.

In contrast, the vast white population in North America meant that rebellions by enslaved individuals, although more frequent than many assume today, posed a less significant threat to white dominance. Consequently, even though fear of rebellions heavily influenced the legal and cultural frameworks of North America, British colonists seldom had to grant legal or political concessions to enslaved people.

Regional and demographic differences also shaped the development of race and racial hierarchy in North America. For instance, in the first century of Portuguese colonization in Brazil, the shortage of Portuguese or white women led to frequent interracial relationships between white men and women of African descent, despite anti-miscegenation laws in Brazil. By 1822, over 70% of Brazil’s population was composed of blacks, mulattoes, slaves, freedmen, and free people of color.

Today, Brazil is home to the largest population of people of African descent outside Africa.

In most South American and Caribbean colonies, sizable populations of free people of color emerged, leading to the development of intricate systems of racial and caste classification. Conversely, North America had a different racial hierarchy, where free people of color represented a tiny fraction of the population. The region was divided by a rigid color line separating Black and white groups.

Finally, the legal codes governing the lives of enslaved people—such as regulations on manumission, the legal status of enslaved individuals as humans or property, marriage and family rights, and racial classification—varied across regions and colonies. These laws reveal the complex racial hierarchies that existed in the area.

Throughout the region, laws explicitly prohibited free Black individuals from holding political office, practicing prestigious professions (such as public notary, lawyer, surgeon, pharmacist, or smelter), or enjoying equal social status with whites. However, in 1795, the Spanish Crown introduced a policy allowing people of color with mixed ancestry to “apply and pay for a decree” that legally changed their status to white. These laws sparked intense and serious debates over the civil rights of individuals of mixed heritage in some countries. The 1812 constitution of the Spanish Empire further extended opportunities for mixed-race citizens, including desegregating universities, long before similar advancements in the U.S.

In French colonies, the “Code Noir,” enacted by Louis XIV in 1685, significantly influenced the societal landscape. It prescribed the death penalty for enslaved individuals who attacked their enslavers. Conversely, it also recognized free people of color as having the same rights as any “persons born free.” The code forbade the sale of enslaved parents separately from their children and regarded the child of a free woman and an enslaved man of color as free. Additionally, it imposed a fine on enslavers who fathered a child with an enslaved woman unless they married and freed both the woman and her child.

Significantly, under the Code Noir, the population of free people of color grew significantly. By 1860, Louisiana, which was under French control for many decades, had 18,647 free Black residents—nearly 3,000 more than the total in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi combined.

The British and their descendants in North America shaped laws around race, making it the key factor in the regulation of slavery and the lives of both enslaved and free Black Americans. A clear “black-white binary” highlighted and reinforced how race was central to all aspects of American society.

Consequently, although the specific experience of slavery varied by region and era, in the U.S., it evolved into a strict, racialized caste system that permanently linked slavery to race.

The enslavement system in North America was legitimized by a complex set of laws enforced through violence and terror, aiming to justify and codify the lifelong, hereditary, and perpetual slavery of Black people across generations.

Since the first kidnapped Africans arrived in what would become the English colonies and later the United States, slavery was central to the economy of every major city on the Eastern Seaboard. Understanding the history of these regions requires recognizing how enslavement contributed to their economies, laws, and political and cultural institutions, as well as the many ways this legacy continues to influence these communities today.

Equal Justice Initiative, “The Transatlantic Slave Trade” (2022).

WORLD COLONIZATION MEMORIAL MUSEUM

Mission

World Colonization Memorial Museum’s mission is to restore and make visible suppressed, destroyed, or underrepresented histories of colonization worldwide. It will provide a comprehensive compilation of world history, focusing on the legacy of colonization.

A reflection space honoring those who have worked to challenge colonization around the globe

World Colonization Memorial Museum (WCMM) will provide an in-depth examination of colonization, covering topics such as the Age of Discovery and Exploration, the conquest and subjugation of Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, Asia, and the brutal Transatlantic Slave Trade and its impact. The museum will also address the various genocidal wars that occurred during the decolonization process. Through films, images, and first-person narratives, visitors will experience detailed and compelling interactive content.

WCMM will provide an immersive experience, featuring cutting-edge technology, world-class art, and crucial scholarship to explore the dark aspects of world history.

Alongside the world’s first and only international memorial dedicated to the victims of colonization, the museum presents a unique opportunity for visitors to confront challenging aspects of our past.

Colonization in the Americas, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe will feature five interconnected wings in the Museum, showcasing hundreds of sculptures and original animated short films narrated by award-winning artists worldwide.

A dedicated wing of the museum will examine the economics of colonization, the role of the League of Nations, and later the United Nations Trusteeship Council, in the violent enslavement of Indigenous peoples in Trust Territories. It will address issues such as sexual violence against women and children in the colonies, the commodification of people, and the desperate efforts made by colonized individuals to achieve independence.

An extensive exhibit on the brutal assassinations of prominent pro-independence leaders worldwide will document a detailed timeline, short films, and first-person narrative accounts.

The museum’s extensive content on various wars of independence will be located in a wing that explores the role of media during the era of racial terror resulting from colonization.

The final words of war victims will highlight the suffering caused by colonization, affecting entire communities. Details about the starvation of children will help visitors grasp the extent of terror and violence endured by many families.

Visitors will hear firsthand accounts from the descendants of murdered pro-independence leaders and those who lost family members during some of the most devastating wars for independence. They will also learn about the courageous efforts to challenge colonization led by legendary decolonization activists. This includes figures such as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, an Indian lawyer and anti-colonial nationalist known for his nonviolent resistance in the successful campaign for India’s independence from British rule, ,,, and Kwame Nkrumah, the father of modern Pan-Africanism (not exclusively).

WCMM will emphasize courageous decolonization movements that challenged colonization and forced colonial powers to respond. This includes the Wars of Scottish Independence, the American Revolutionary War, the Haitian Revolution, the Latin American Wars of Independence, the European Revolutionary Wars of Independence, the Middle East and Asia Revolutionary Wars, and the numerous wars of independence across Africa.

The portrayal of colonization as a widespread manifestation of racism will be compellingly illustrated through a collection of actual signs, artifacts, memorabilia, and notices from across the globe for visitors to see, read, and experience.

Visitors will learn about significant civil wars worldwide and how their origins stem from the way colonial powers established national boundaries, often forcefully merging different religious and ethnic groups.

A discussion on the disenfranchisement of Black soldiers will highlight the Forgotten Colonial Forces of the World Wars, a crucial element in how equal rights were undermined during the colonization era.

The Berlin Conference of 1884 formalized European claims to African territories and established rules for colonization. This was followed by the League of Nations Mandate, which legalized colonization under international law. The United Nations Security Council has also played a role in perpetuating a legalized caste system, which is one of the most significant legacies of colonization. The WCMM will showcase controversial timelines of colonization and outrageous international agreements that have shocked humanity’s conscience.

WCMM will have a Reflection Space that honors hundreds of people who have worked to challenge colonization.

In a grand space featuring world cultures and powerful imagery, the history of struggle will inspire everyone to reflect on how we can make a difference.

The museum will feature a world-class art gallery displaying major works by celebrated artists from around the globe. We will have a gallery that showcases works created exclusively for WCMM. The entire collection will be curated in relation to the museum’s historical narrative.

Collaborations with Western and non-Western world music, including quasi-traditional, traditional, and intercultural forms, will explore the roles and significance of arts, music, and dance in global decolonization efforts.

As a physical location and outreach program, WCMM will serve as a catalyst for education about the legacy of colonization and racial inequality, fostering truth and reconciliation that will lead to genuine solutions for contemporary issues.

Let's Unveil the Ugly Parts of Our History

Something unjust happened around the world that too few people have discussed. WCM acknowledges that, despite the impacts of colonization, the world can still become a better place. However, if we want to move forward, we must speak the truth, recognize the darker aspects of our history, and commit to reconciliation and healing.

Do you or anyone you know speak English, Spanish, French, Dutch, or Portuguese? Are you aware that these languages, which carry culture and embody the beliefs, values, and identity of European nations, were imposed on conquered populations around the world that were disproportionately of color?

Are you aware that, across Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the Middle East, colonization was not just about economic and linguistic imperialism? It was also a global expression of racism—a brutal and nefarious crime that was witnessed and even celebrated by millions of White people.

Do you realize that the United Nations Trusteeship Council, assigned under the UN Charter to supervise and promote the advancement of Trust Territories toward self-independence, was severely undermined by colonial powers? Under its watch, Trust Territories around the world were drenched in the blood of their revolutionary heroes, who were killed under horrific circumstances—including targeted assassinations, extrajudicial executions, massacres, and genocide.

Are you aware that during colonization people of color were reminded that if they tried to resist enslavement, if they try to prevent the partition of their kingdoms, denied their master’s language, or insisted on gaining independence - in other words, if they did anything that upset or complicates White supremacy, White dominance, and political power they will be killed?

Are you conscious that colonization was not just an uncomfortable footnote in history but reflected the belief in racial differences that reinforced Apartheid, Jim Crow Segregation, and systemic racism that has done real psychic damage not just to Black people but to White people too?

Do you believe that the killing of men, women, and children under the banner of colonization was wrong, unjust, and though most people would rather forget, this dark period of racial terrorism in our past casts a shadow across the world and compromises our commitment to reconciliation and healing?

Regardless of direct impact, if you could, would you do something to commemorate colonization victims and help the world recover from centuries of racial injustice?

If you answer yes to one of the above, you are exactly who we seek. You can become a volunteer or an intern by sending us an email: info@wcm-m.org

You can also connect with WCM through our social media platforms below.

Business:

The international business community is embracing corporate responsibility and can work with us to heal racism and make the world a better place. Partnering with WCM to help tackle racial injustice is good for global citizenship and good business.

Don't hesitate to get in touch: info@wcm-m.org

Civil Society:

WCM recognizes the importance of partnering with civil society/non-profits and invites you to join us in building a better, safer, equitable, and more sustainable world.

Please get in touch: info@wcm-m.org

Donate:

Do you want to contribute to the world's first and only colonization memorial?

World Colonization Memorial (EIN 86-3844927) is a 501(c)(3) organization. Gifts and donations are tax-deductible to the full extent allowable under IRS regulations. You can support us by donating via our Donate link above.

Connect With Us

Please connect with WCM through our social media platforms below.